Joseph Sternberg the Theft of a Decade Review

In The Theft of a Decade: How the Infant Boomers Stole the Millennials' Economic Time to come , Joseph C. Sternberg argues that the predicament facing Millennials today – including job precarity and difficulties entering the housing market – is not of their own doing, but rather the consequence of poor policy decisions taken past the Babe Boomer generation that accept only been exacerbated by the 2008 fiscal crisis. Sternberg weaves a compelling and rich tapestry of historical context, political controlling and economic examples to explicate the Millennial experience and to entreatment to the Babe Boomer generation to recognise the consequences of their mistakes, writes Sumaiya Rahman .

If y'all are interested in this book review, y'all may similar to listen to this 'Extra Innings' episode of The Ballpark podcast in which Joseph Sternberg talks to Ballpark host Chris Gilson about his book.

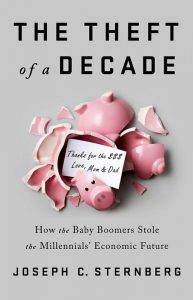

The Theft of A Decade: How the Baby Boomers Stole the Millennials' Economic Future . Joseph C. Sternberg. PublicAffairs. 2019.

Notice this volume (affiliate link):

Notice this volume (affiliate link):![]()

'How is it that the Baby Boomers who are bequeathing their children such a comfortable today have also managed to steal those children's tomorrow out from under them?'

In The Theft of A Decade, Joseph C. Sternberg begins by pointing at the paradox facing Millennials today: daily life is easier, safer and more comfy than e'er before, just finding a job with long-term security, or purchasing one's beginning house, is much harder. Sternberg, a member of the editorial lath at the Wall Street Journal, asserts that this predicament is not of the Millennials' own doing, simply is in fact an issue of the poor policy decisions taken by the Baby Boomer generation. He breaks down the historic events that led to the current economic environs as an appeal to the Infant Boomers to recognise their mistakes and let the Millennials an opportunity to solve their own troubles.

It is probably all-time to start out by defining who the Millennials are. As Sternberg puts it, Millennials are older than most people realise – the oldest are somewhere in their belatedly thirties or early on forties and the youngest have either only finished schoolhouse or graduated academy. This ambiguity is because in that location is no clearly defined start or cease point to the Millennial generation (sometimes as well referred to equally Generation Y), unlike the Baby Boomer generation which ran between 1946 and 1964. What defines a Millennial, as Sternberg states, is the one experience that they all share: their developed lives have been overshadowed by the events following the 2008 global financial crisis. The early Millennials, like Sternberg himself, were lucky to have gotten their offset jobs before the financial crisis. The majority of the Millennials, however, have only known the labour market during the 'deepest recessions and the slowest post-recession recovery in American history'.

A common assumption before the financial crisis had been that the lowest-paid, lowest-skilled jobs were the most vulnerable to economic fluctuations. To an extent this is true – low-skilled routine jobs accept been on the decline regardless of the economical surround. However, during the financial crisis, it was actually the mid-wage jobs that took the greatest hit. The share of mid-wage jobs as a proportion to overall employment shrank between 2007 and 2013. As a result, the older mid-tier workers, typically of the Baby Boomer generation, have moved down the career ladder, pushing out the Millennials who were just starting out.

The reason behind the poor labour market atmospheric condition is that the government prioritised 'debt-fuelled, short-term growth' over 'task-creating' investment. The short-term involvement rates had been low for several years, and 'quantitative easing' pursued equally a response to the fiscal crisis aggressively reduced the long-term interest rates every bit well. Together, this made it more than lucrative for companies to engage in debt-funded share buybacks rather than make long-term investments in labour. Making matters even worse was the Affordable Care Act that tied insurance to employment, making labour even more expensive. Thus, Sternberg demonstrates, the starting time major theft by the Baby Boomers.

The focus on low-interest rates and cheap financing didn't only prevent the Millennials from entering the labour market; it also finer created an entry barrier in the housing market place too. This is the chapter where Sternberg is at his finest. Sternberg points to several shows that Millennials grew up with, from Home Comeback to MTV's The Real World. These shows highlighted what it means to own holding: 'Owning your home is the sign that you've fully ''arrived'' in adulthood.' Unfortunately, while even the youngest Millennials are now adults, few have 'launched'.

In 1990, when home ownership among younger buyers of the Baby Boomer generation fell by three percent points over the last decade to 57 per cent, politicians were rightly concerned. They feared that likewise many people, especially those amidst the less privileged, were missing out on the benefits of dwelling house buying, the principal course of wealth aggregating over the decades. In an endeavor to rectify this consequence, the U.s.a. Congress lowered lending standards and aggressively pushed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to get as much as fifty per cent of their loans to low- or middle-income borrowers. When interest rates were cut following the bursting of the dot-com bubble and the 9/11 terror attacks, the market for mortgage-backed securities (MBS) took off. The mortgages at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were considered 'rubber', were available in large supply and offered college returns than other markets.

There were trillions of dollars' worth of mortgage-back securities available for investors to buy, they were supposed to be safe, and they offered a higher rate of return when returns for many other assets had been driven downward by low Federal Reserve interest rates.

Sternberg's commentary on this serial of events is rather poignant. The value of domicile ownership is through its aggregating of disinterestedness, 'helped by an amortizing mortgage requiring a substantial down payment'. By lowering the lending standards, the government had boosted housing debt rather than housing equity, nether the simulated conventionalities that housing prices would ascension indefinitely. They did not. As the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates to cool downwardly the economic system, mortgage rates crept up, and house prices stagnated. What followed was 'a especially wretched scrap of financial history' that has shaped much of the Millennial experience. The consequent policies taken by the government were aimed at 'saving the housing for those who already owned homes', and that is where the trouble starts, asserts Sternberg. Through the propping up of house prices, the availability of refinancing opportunities and the strengthening of financial regulations, the Millennials are now locked out of the housing market.

In The Theft of a Decade, Sternberg weaves a rich tapestry of historical context, political decisions and economic examples to explain the predicament for Millennials today. At times, this tin can feel quite overwhelming, which Sternberg alludes to himself. About two-thirds of the style into the book, he provides no 'bulleted list' or 'a plan for a law' to solve any of the problems he discusses facing the Millennials. Instead, what he hopes to do – and in some chapters, he has definitely achieved – is to 'hint at solutions' past discussing these issues in particular. In this sense, The Theft of A Decade is not about putting forward new ideas, but about presenting a compelling summary of the conversations the Millennials are most interested in having.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and non the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a minor commission if y'all choose to make a purchase through the aboveAmazon chapter link. This is entirely contained of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Prototype Credit: Image by Kevin Schneider from Pixabay.

Source: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2020/02/17/book-review-the-theft-of-a-decade-how-the-baby-boomers-stole-the-millenials-economic-future-by-joseph-c-sternberg/